On here, I write about railways. It is, shall we say, a very specific kind of person who would do that. That sort of person (me) has a tendency to get bogged down in minutiae; what things went where at what time travelling on what things commanded by who, and that’s where the general audience falls asleep.

And that’s why I try to do things a bit differently here. What’s still here? What was here? How does what is here connect to what was here? And what does the difference between the two mean? If I answer those questions well enough, I might be able to make a web page about a minor station in a village in Norfolk interesting.

Anyway, here are some words illustrated by some pictures.

When you first arrive at Watlington, the last stop on the Fen Line before King’s Lynn, you’ll probably arrive at platform 2 (the “down” platform), so that is where we will start.

And from that, you could conclude that this is a station in the middle of nowhere with nothing to see, and get back on the train. Well, ignoring the disused Victorian station building and platform on the opposite side, but we’ll get to that, I promise.

Take a look at these railings towards the forward end of the platform.

The uprights are clearly made of old, presumably life-expired bullhead rail, with poles shoved through them horizontally. This style of fence was a simple and effective expedient, common in the Grouping days (1923-1947),1 which is where I shall provisionally date them; more precise dating isn’t possible without more photographic evidence. This style of rail was universal on the railway network (on the railway tracks themselves) from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century; the newer flat-bottomed rail is just as universal across today’s railway network.

The flaking paint, though unattractive, also has a story to tell – one of the various re-brandings that have happened over the years. As other, newer layers of paint flake away, the old Network SouthEast red is once again becoming the most prominent colour on the horizontals. We’ll see more Network SouthEast elsewhere at Watlington.

Walking to the far end of the platform, similar to Downham Market, there is clear evidence that this platform was once about half its current length.

If you don’t notice the change in surface when looking at it, you might notice the change of sound when you walk on it. The older front half of the platform is tarmac on top of compacted earth with brick retaining walls, and the newer rear half is of wooden construction with plywood on the top. For most of its life this platform was about 50 metres long; about long enough to safely disembark passengers from two modern carriages.2 This was extended rearwards – that’s the wooden section – at a date unknown in preparation for the then-new four-car electric trains which took over the line in 1992.

On the extension you will find two Network SouthEast-era benches, a reminder of the era in which this section of the platform was constructed.

They’re a very distinct Network SouthEast feature, specified in the Network SouthEast Design Guide and almost universal on NSE in the past. But you’ll find them at some stations outside the NSE region too,3 and occasionally in places that are not stations. It is the Maceman & Amstad 011 and you can probably still buy one new if you want one badly enough.

Elsewhere on the platform, there is this shelter.

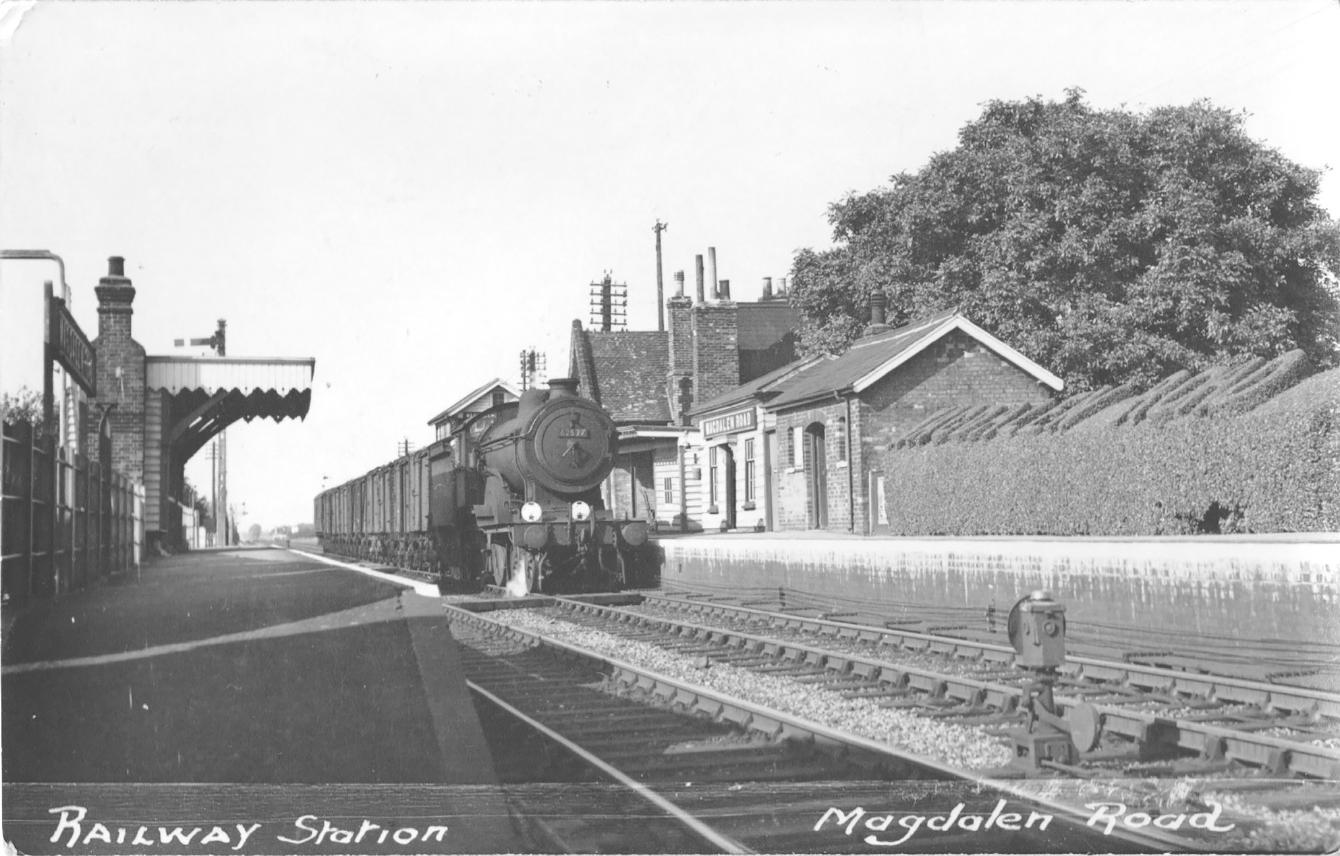

It’s not very interesting. But it’s actually the third passenger shelter in the same place. The original was a cosy-looking wood-and-brick affair, seen in the photo below from the East Anglian Railway Archive in 1978.

This was replaced in the 1990s with a domed shelter identical to the one on platform 1, which was rather good at attracting mould to its curved, glazed roof. That was replaced in the early 2020s with the thing you see today. It is neither warm nor comfortable, but it does keep the rain off and it’s probably very cheap to maintain.

Adjacent to the fence on this platform is the car park.

I’ll try my best to make a car park interesting!

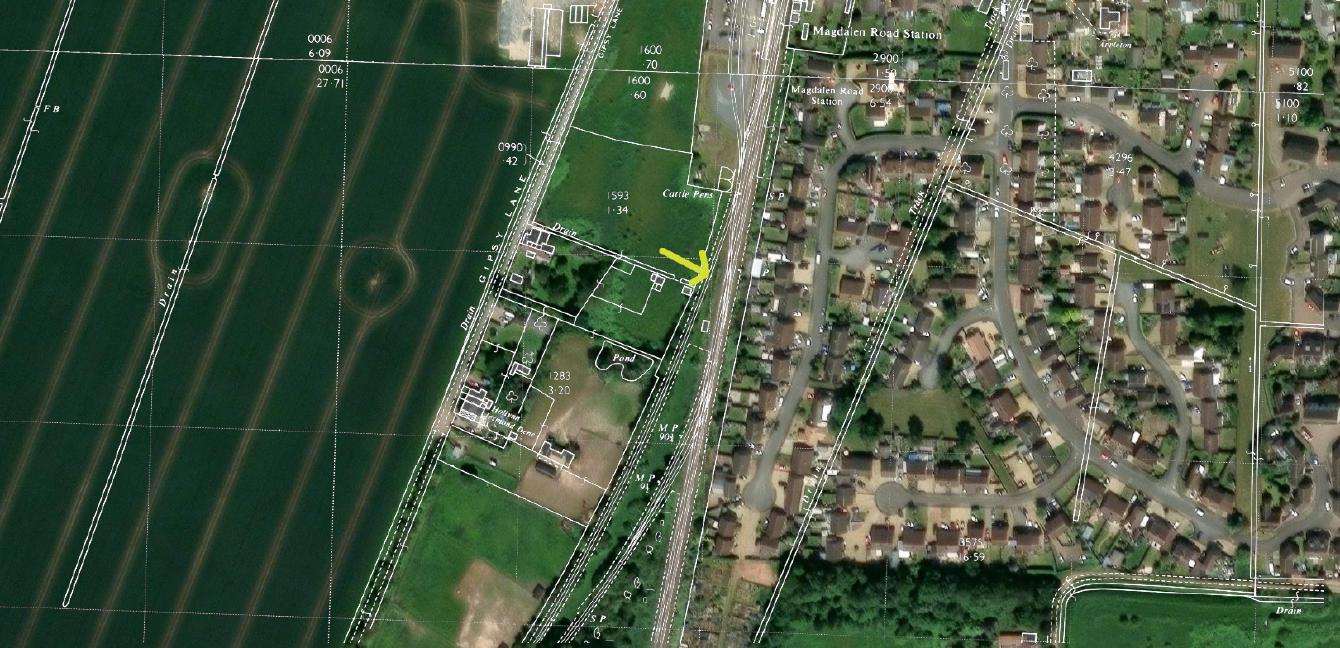

As with many station car parks, this was once the site of the station’s goods yard. The boundaries of the yard are more-or-less tracked by the area of this car park plus the separately-operated, crudely-surfaced (but much cheaper) car park adjacent to it, as you can see in the composite map below.

Consider that Watlington might not be very large today, but it was only a few hundred people in the middle of the 19th century.4 A walk from the station through to the centre of the village will show that most of the architecture is distinctly 20th-century, with the old station building (I’ll get to that soon, I promise) a conspicuous outlier. Watlington station was built at the height of Railway Mania in 1846, a boom-and-bust comparable to that “.com” thing in my lifetime (and maybe the put “AI” in a press release and watch the stock price go up thing today; we’ll see).

Railways were not always built to match existing traffic flows; stations were often built and then the traffic found them. In the railway boom peaking in 1846, this might been less “if you build it, they will come” as it was “if you take the money to build it, you can walk off with the money”, or “everyone else is building them so why not”. Often, the traffic didn’t find them, and then they closed not long after, as happened to the stations near Runcton Holme (Holme station) and Wiggenhall St German’s (St. Germain’s station).

Consider too that the commute did not exist in 1846 either; most people worked within walking distance of where they lived, because they had to. Commuting didn’t really kick off on Britain till the early 20th century. That was enabled by the growth of the railways, in the same way the existence of this web page and the Internet connection you are using to read it was enabled by the dot-coom boom, but it took a while for lifestyles to adapt. Combining the tiny population of Watlington with the fact that most people had little need to make a journey of any kind, we can see that passenger journeys were, for a long time, not a meaningful source of traffic for the station.

What did prove to be lucrative for rural railways was freight; in particular, food for the rapidly-growing cities. That’s why even the smallest stations almost invariably had a goods yard, and why many stations closed to goods some time after they closed to passengers (even the aforementioned St Germain’s, closed in 1850, retained a goods siding well into the 20th century).

Goods traffic at smaller stations went away due to a combination of changing freight patterns (larger trains with less varied loads) and the rise of road transport, but some stations were fortunate enough to see a rise in passenger traffic caused by a growing population and “the commute”. And so, I think the car park at Watlington has more to say about it than “well, they paved over the goods yard and isn’t that a shame”.

Looking out the bottom (southern) end of the cheaper car park, you will find this suspiciously straight and clear track. You could be forgiven for thinking that this was the path of the former line to Wisbech.

But this actually tracks a long siding (about 350 metres) that extended its way south-ish from the station then curved around following the Wisbech branch but on a slightly tighter radius. The junction with the Wisbech line is just a short distance south. In the first picture above, the siding is tracked by the line of shrub and then tree on the right hand side; in the second, on the left. It’s indicated with a yellow arrow below (best viewed at full size to avoid aliasing artifacts on the fine lines).

On the other end of the car park next to the road, there’s this nice little building in the car park, near the level crossing. Given its location, and the chimney (implying a fireplace, which implies human occupation) we could guess that this was an office for the goods yard. It’s still owned by Network Rail as far as I can tell; it sees periodic maintenance like removal of ivy.

Next to that is this substantial gate post.

That was presumably for the entrance gate for the goods yard. A siding once crossed the road separately from the main line, and it would be tempting to think that this post was for the crossing gate. But maps (like the one earlier on this page) suggest it crossed the road on the other side of this building.

If you look up, you’ll see the totem sign.

Which is still carrying Network SouthEast branding! This sign has outlived not just Network SouthEast (1986-1994), but two rounds of the private train operating companies which replaced it (WAGN, then First Capital Connect; today it’s Great Northern). Depending on what happens with Great British Railways over the next few years, it might outlast the concept of a train operating company entirely.

Crossing the road, you will not miss the signal box.

It is often noticed, and mentioned, that the signal box carries the station’s old name of Magdalen Road.

The short version is that the signal box is still officially called Magdalen Road, but that gives an opportunity to talk about the station’s name.

Watlington was named Watlington from its opening in 1846 until 1875. In 1875 it was renamed Magdalen Road – apparently without notice, to the consternation of probably two people5 – presumably to avoid confusion with the Watlington station in Oxfordshire, which opened in 1872.

Keith Skipper’s Hidden Norfolk contains a story – not designated as apocryphal – about the station being renamed due to the intervention of a “city gent with friends in high places”:

Watlington was given a new name after that city gent boarded the train at Liverpool Street and asked for…Watlington station. He duly arrived and discovered he was not in the village of Watlington in Oxfordshire as he had hoped, but in dear old Watlington in Norfolk. Complaints were made. The name was changed to Magdalen Road.6

I like the story, but it is probably best understood as a record of community memory and folklore rather than historical fact. It follows Victorian popular literature’s trope of gentility’s ignorance about the workings of the railways.7 And it takes the form of a classic city-vs-rural comeuppance where city, according to rural, turns out to not be as clever as they think. The real reason was likely dull and bureaucratic; communities need stories like these to bring a massive, impersonal system down to human scale.

Whatever the real reason for the renaming, the Magdalen Road continued through the station’s closure in 1968 and then re-opening in 1975. It was renamed back to Watlington in 1989; this coincided with the closure of the last section of Oxfordshire’s Watlington and Princes Risborough Railway in the same year.8

Returning to the sign on Watlington’s signal box, then. This is not an oversight; British Rail did not forget to change the sign on the signal box. Rather, it was decided to not rename the signal box, to avoid the expense of updating the signalling system and documentation.9 Thus Magdalen Road signal box continued with its old name, and is still officially called Magdalen Road today.10

This box is still in use, and closure has seemed imminent for a long time now; the traditional signal box is increasingly made redundant by digital signalling from massive centralised signalling centres. This has been threatened for long enough, in fact, that one might start believing that this signal box in particular is not really endangered (which it is).

At its current location, this signal box dates from 1927. But this is actually a Great Central Railway type 5 signal box from the late 1890s, relocated here in the LNER era.11 Compare Magdalen Road with, e.g., Rothley Cabin on the preserved Great Central Railway in Leicestershire, in the picture below. The design similarities are clear, especially the small square window just below the apex of the roof (blanked off at Magdalen Road, but you can clearly see where it used to be).

Other than a repaint and a rebrand from time to time it does not seem to have changed much externally over the years; the most obvious change is the removal of the balcony used for cleaning the signal box’s windows. That disappeared when overhead electrification wires appeared, for reasons that are very obvious if you think about it.

Elsewhere on the level crossing you will find a few of these British Rail-era signs warning you against trespassing; a very common survivor on smaller stations, and some larger ones too.

These were, in recent years, supplemented by much uglier modern signs, likely designed in Microsoft Word with input from at least 4 different people who not only knew nothing about designing public signage, but were actively hostile to restraint and good taste. I refuse to dignify those with a photo. The fact they are disintegrating while the simple British Rail signs continue to exist feels like even the laws of physics can’t stand the sight of them.

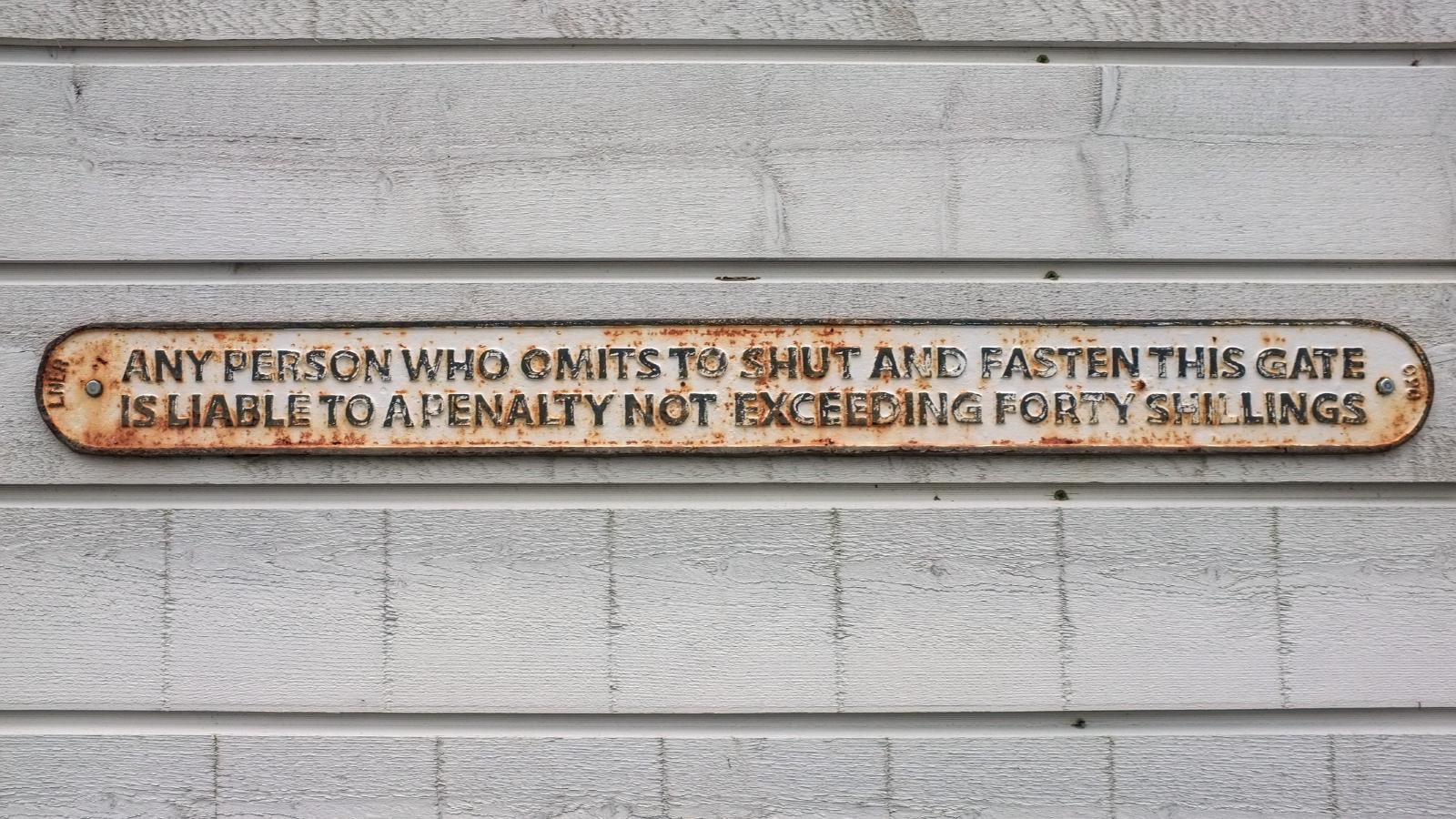

Also on the level crossing is the former foot crossing adjacent to the road.

That used to permit pedestrians to cross the line while keeping some distance from the cars crossing at the same time. It also used to be latched separately from the road barriers; Often if you were running a little late and missed the main barriers closing, a kind signalman would unlock the gates to permit you to get to the train on the platform on the other side of the track. I suspect, but do not know, that this is the exact reason the gates have been locked out of use, and have been for some years; railway management is often not fond of allowing some discretion.

The gates remain, though, and so do the counter-weights which used to pull the gates shut. It’s a nicely over-engineered alternative to a spring.

Though the gates are locked, there’s nothing stopping you from getting right up to them (on the safe side, obviously). That means they’re a pretty good place to watch the trains go by while not getting in the way of anyone.

And so, we can get to the old station buildings that are right next to this gate.

But first, Richard Beeching.

I’ll write more on him some day; now that over sixty years have passed between his report, I feel that we’re overdue for a discussion of him and the railway cuts of the 1960s that goes beyond cartoon villains. Actually, that was going to be right here, on this page, in the middle of an article about a station in a Norfolk village, but somewhere in the middle of writing the tenth paragraph I thought “oh, this is a rather long aside even by my standards”.

So to keep it relevant to this page: Magdalen Road was never suggested for closure in Beeching’s report. It closed anyway, on September 9, 1968, along with the line towards Wisbech that branched off at the station – and note that this was three years after Beeching left the British Railways Board. Much gets attributed to “Beeching’s axe” that either predates or postdates his tenure, and a substantial number of lines & stations were closed which were not mentioned in Beeching’s report.

If we care about the truth, we shouldn’t attribute more things to Beeching than he did or said.

On to those buildings! Here is the old station house.

The station buildings were sold off by British Rail in 1972, after the station’s closure in 1968.12 They stayed with the same owner until the wonderful Laura, who invited me to have a look around the old buildings, purchased the old station in December 2020.

I think everyone who likes railways likes the idea of living in an old station. The reality of it is that, in this case, it is a building that will be two hundred years old well within my lifetime if my lifespan follows the statistical mean. Internally, the main station house was falling apart when Laura bought it, and she has done significant work to ensure its integrity; less “this building has its issues” as we often hear about, e.g., new builds, and more “this thing might not be standing if it is not fixed immediately”.

This is not the only reason I envy the task far less than I envy the idea of living on a station (one that is a ten-second walk from the line I commute on, too). Historic railway buildings invariably attract people with opinions, opinions that are easy to generate when one is neither spending the money to implement those opinions nor having to make whatever compromises are necessary to have a place to live. And what I actually mean by that – and I say this as a fan of railway history, far more so than about the 99% of people calling themselves that whose primary contribution to it is “dumping half an opinion into a Facebook comments section” – is that Laura has sunk huge amounts of money into saving the former station (as said, it actually did need saving) and turning it into a home for herself and her family, and anyone who would criticise her for it can absolutely, categorically get fucked.

Anyway, carrstone walls!

And this beautiful doorway (which is now a window; the age of the bricks underneath it show that they are a later addition).

Which has this curiosity on the side. It very much has the form of once being a window which has been bricked off. Yet the brickwork is old enough, and consistent enough with the brickwork around it, that makes me think this might have been a fairly early change in the building’s life.

Even one of the drain pipes is beautiful.

On the platform side is this mystery bracket.

And this former waiting shelter; the regular, machine-made brick suggests a different configuration of this area in the distant past.

Next the sympathetically-restored ladies waiting room (and a reminder that I need to re-visit with a wider-angle lens).

And what is likely the former lamp room and general store.

Next is the hedge.

In the past this had the text “Magdalen Road” impeccably cut into it – an idea probably copied from another Great Eastern Railway station at Snettisham.

But the hedge hides a secret: there’s more bullhead-rail-and-pole fencing, identical to that on platform 2. Again, this is likely to be a Grouping-era expedient.

Looking back down the platform, we can see that it is very narrow.

But the evidence shows that it was somewhat wider at some point; it was likely rebuilt for extra clearance after the new platform 1 was opened, evidenced by the modern blocks on its face (this was previously brick-built).

In fact, it was actually somewhat longer than it is today, too. Older diagrams of the station shows that this up platform was somewhat longer than the pre-extension down platform, but the old up platform is today somewhat shorter.

The back garden…

…gives us an opportunity to compare the boundaries today with the boundaries of the station as it was in an earlier era; you can see that the current east boundary is a recent change, and a newer house occupies about half the space of the old station garden.

And also affords a rear view of the old store room.

Isn’t it nice?

As said, the station closed in 1968. A local campaign to re-open it was led by former signalman and World War II submarine veteran13 Ron Callaby from Narborough. British Rail did not oppose the idea, and the case for it was made stronger by the rapid growth of Watlington.

But the £500 or so (in the region of £5,500 in 2026) would have to be raised locally, and the parish council would not fund it either.14 Local fundraising – via donations, tombolas, and dances15 – was successful, clearance and tidying and painting were largely performed by local residents, and the station re-opened in 1975, using the original platform 1 (minus its buildings, which as mentioned had already been sold) and about half of today’s platform 2.

The old platform 1 might have sufficed for the somewhat minimal service running through Magdalen Road after the 1975 re-opening,16 though it rather precluded any passenger growth. It was too low and too narrow17 for a modern service and the expected rise in traffic that electrification would bring (an expectation that was met). A new platform was built on the site of former sidings behind the signal box, which is the one in use today. The old Platform 1 saw its last service in July 199218, with the replacement platform being pushed into service immediately after19.

The overhead wires were turned on the next month20, bringing in an era of rapid four-coach electric trains all the way through to London.

And for some, that means the end of interesting trains on the Fen Line – the end of locomotive-hauled passenger services. But we should remember that most of Watlington’s services before 1992 were actually tiny, ancient, loud 2-car DMUs. Those are interesting enough in their own way and I like them in exactly the same way I love a Pacer. I’ll happily take a ride on one on a heritage railway; if offered the option of using one regularly as transport I’ll get in the car.

By comparison, any electric train rules.

Today, Watlington is a village with a couple of thousand people in Norfolk that gets half-hourly electric trains in the peaks! If we are to declare some golden age of Watlington station in particular and the Fen Line in general, I argue that it started in 1992. Electrification of the Fen Line was an unqualified success for passengers; it brought a frequency of trains that would have been unimaginable at any other time in the line’s history, and passengers responded by using it in numbers that also would have been equally unthinkable in the past.

With that said, I’d really like some padding on the seats, please.21

Our walk towards the “modern” platform 1 will take us past this “Private” sign on the gate to the signal box on your walk there. (I originally wrote that without the quotes around “modern”, before I realised 1992 was 34 years ago – a fact that horrifies everyone born in the early 1980s.)

This dates from the Network SouthEast era again. Underneath it, with just its corner visible in the photo (this is not an accident) is a Network Rail sign saying exactly the same thing in 18 times as many words. A consistent, tasteful system of signage actually was better in the past! RETVRN!

If you look up at the signal box, you’ll find another Network SouthEast sign on the rear near the entrance door bearing the “Magdalen Road” name.

This one carries no less than three brands! There’s Network SouthEast blue text, the oldest of them. WAGN purple was pasted on top of the NSE stripe on the bottom, then later First Capital Connect covered that over, and finally FCC was blanked out with blue some time after that company was replaced with Great Northern. Maybe Great British Railways will add more to it in future. We’ll see!

On to the platform.

I’ve saved this for last, because it’s the part of the station giving me the least to discuss. It’s a basic platform, using identical wooden construction to the extension on platform 2, long enough for four modern carriages.2 There aren’t any historic artefacts on it. There is this waiting shelter, though; as mentioned, the one on platform 2 used to be identical.

That is distinctly late-80s to early-90s in style; it bears more than a passing resemblance to early Docklands Light Railway platform shelters. This was a somewhat later addition; this platform opened without a shelter.22 These days at peak times the station is often too busy to fit everyone into the shelter anyway, so for some number of people it might as well not have one.

And finally, one more artefact from the near-past. The mirror at the forward end of the platform is still painted Network SouthEast red (and there’s an identical one on platform 2).

These are redundant now that today’s Electrostar units have cameras for safe driver-only operation. For as long as they exist, they’re a nice reminder of the Network SouthEast EMU era.

Key dates

- 1846: opened (26 October)

- 1875: renamed to Magdalen Road (1 June)

- 1968: closed (9 September) along with the branch to Wisbech the same day; Fen Line through it remains open

- 1975: reopened (5 May)

- 1989: regained pre-1875 name of Watlington (3 October)

- 1992: last train into old up platform (12 July), opening of new up platform (July)19, electric trains take over passenger services (22 August)20

-

Information from Daniel Wright. ↩︎

-

“Modern” here means 1951’s British Rail Mark 1 coach onwards. These were typically 19.35 metres long; almost every other carriage & multiple unit car since then has similarly been in the ballpark of 20 metres long. ↩︎ ↩︎

-

For example, they show up in photos at Wymondham and Swinton (South Yorkshire) – the latter being far outside the Network SouthEast area. ↩︎

-

White’s History, Gazetteer, and Directory of Norfolk records it as 502 people in 1845, before the railway, and 577 in 1854. Bradshaw’s Handbook for Tourists in Great Britain & Ireland records the population as 659 in 1858; the discrepancy between this and other numbers available might indicate a different method of counting it. ↩︎

-

John Thorley, Letter to the Editor in the Lynn Advertiser, July 3, 1877. ↩︎

-

Keith Skipper, Hidden Norfolk, Countryside Books, p. 139 (ellipsis in original). ↩︎

-

The Mistake of Going on Holiday: Travel, Tourism and Leisure in Early and Mid-Victorian Illustration ↩︎

-

But might not have been caused by the Oxfordshire line’s closure, as I have seen claimed. That last section of track was freight-only in its last days and only ran as far as Chinnor; Watlington in Oxfordshire closed to all traffic in 1961. ↩︎

-

The description of a signal box diagram from Owen Stratford explains that “the signalbox was to follow suit until the cost of updating all of the signalling documentation and equipment was realised”. The photo carries the interesting detail of the renaming having actually been added to the diagram at one point, then covered over. ↩︎

-

See, e.g. the Anglia Route Sectional Appendix as of December 2025. ↩︎

-

See Context and Knowledge for Functional Buildings from the Industrial Revolution Using Heritage Railway Signal Boxes as an Exemplar. ↩︎

-

From the deed of sale sent to me by Laura. ↩︎

-

“Station’s forgotten hero remembered”, Lynn News, 20 May 1997 p. 4. ↩︎

-

Lynn News & Advertiser, 4 December 1973, p. 5. ↩︎

-

Railway local history on the Watlington Norfolk website. ↩︎

-

The Lynn News of 9 May 1975 records the weekday times of trains to King’s Lynn as 06:07, 08:45, 10:37, 16:37, 18:16, 20:40, and 22:54. By 1985 the British Rail timetable says 08:08, 10:27, 11:58, 13:58, 15:09, 16:52, 18:32, 20:36 and 22:39. Compare with the half-hourly peak and hourly off-peak service we have today. ↩︎

-

Lynn News, Friday 24 July 1992, p. 31. ↩︎

-

A Facebook comment from Gary Dyble says he drove the last service to call at the original platform: 2H95 on 12 July 1992. ↩︎

-

A special section of the Lynn News from Friday 24 July 1992 describes the new, longer platform 1 at Watlington. We know that the last service into the old platform was Sunday July 12; this is as precise as I can date the opening without further evidence. ↩︎ ↩︎

-

railwaycodes.org.uk has the date of the first service as Saturday 22 August 1992, with a full service beginning that Monday. ↩︎ ↩︎

-

My criticism will date badly. As I write this the Class 387s are gradually being replaced by near-identical Class 379 units. They’re both very nice trains (especially the arm warmers, a feature that should be mandatory for every new train), but the 387s have borderline-ironing-board seats and the ones in the 379s are very good, especially in first class. ↩︎

-

The first complaint I found about the new platform appeared in the Lynn News from Friday 23 October 1992, about a lack of a shelter on platform 1; the 21 May 1993 printing (p. 20) says that one still hadn’t arrived at that point. ↩︎