Let’s get straight to the good part: Network SouthEast.

The Network SouthEast signage at Downham Market is not from the Network SouthEast era. It appeared some time in early 2017, and that was the best surprise I ever had on my commute to Cambridge. It was not for purely nostalgic reasons that I was delighted, though of course there was that too (Network SouthEast was a significant part of my childhood). I was pleased that Network SouthEast was getting some of the public recognition it deserved.

You can read about the history of Network SouthEast elsewhere. What I’ll do here is talk about two possible approaches to railways in Britain, of which the Fen Line and Downham Market are a microcosm.

- The railways are not popular, so let’s rationalise and cut costs to stop them losing so much money.

- Let’s make the railways good, so that people want to use them, and then they will make more money.

With the first approach, there’s little point in investing in railways, because people do not want to use them. The only sensible thing to do is to cut services and downgrade rolling stock to the smallest possible units that can be used. The stations don’t need much attention either, because few people are using them. We can call this “managed decline”.

In the second, you make the services as good as reasonably possible. You electrify, you ramp up timetables to the maximum reasonable capacity, you make stations attractive. You upgrade trains, and you make sure they run on time.

The first approach was what we saw most of the time for most of the life of British Rail (and seems to be the default mode for railway management in this country today). People who like railways often confuse this with cartoon-villain bad guys who are, to use the usual phrasing, “looking for excuses” to close railway lines – a narrative that makes sense if, and only if, you entirely discount the idea that bureaucracies lack imagination.

And the second approach was Network Southeast. In just a few years (we must remember it only existed from 1986 to 1994) nearly the entire Southern network was transformed. There were of course the bright liveries and branding, considered garish at the time by some (and even those who like them would admit that they are rather bold). Stations were refreshed, and more importantly, services were ramped up. Chris Green, in The Network SouthEast Story, describes this as a mission to “roll back Beeching”. Understood as a rejection of stagnation and managed decline (of which Dr Beeching was mostly just a messenger), that was not at all hyperbolic.

Those of us who like trains-as-such might wish to return to the era of interesting traction on the Fen Line; Class 47s, Class 37s, Mark-Whatever carriages with actual padding on the seats, that music from the Hovis advert and the rest. For people who wish to use the Fen Line as transport, today’s frequency and speed of services would have been unthinkable in the mid 1980s. In fact, for anyone in the mid-1980s, it might be more surprising that the Fen Line still exists; it spent two decades shadowed by the threat of closure.1 By 1985 the service was thoroughly degraded. There were nine trains a day, with services running hourly in the peaks – but weekend off-peak timings had up to three hours between services.2

Nobody could use a service like that for transport! Not to a job, or to any place else that would care if you arrived three hours late because one train was cancelled. That rhymes with the familiar doom loop of “services aren’t used very much, so downgrade the services, which makes people use them even less”, which usually continues all the way through to closure of the line.

What changed was Network SouthEast. Network SouthEast, as said, brought a revamp of all the stations on the Fen Line (and an eagle eye will spot a few extant remnants of the rebranding scattered across the line even in 2025). But it also brought electrification, and electric trains, and a frequent service, and trains all the way through to London. In the “managed decline” philosophy of much of the British Rail era, this might have seemed like insanity. Why bother, if nobody is using the trains?

Time has proved that the upgrades to the Fen Line were a massive success, that a better service brought more people to use it,3 and that closure would have been short-sighted. Network SouthEast almost certainly saved the Fen Line north of Ely, and Downham Market station with it. I am glad that Network SouthEast is being celebrated, because it is is worth celebrating - far more than the “hot dog” totems and Gill Sans that seem to be the default way to celebrate “heritage”. And Downham Market, as a station on a railway line rescued by NSE, might be the most worthy place to celebrate it.

So, let’s have a walkabout.

As you walk from the car park next to platform 2 you will find this nice little siding.

This is a survivor of Downham Market’s former goods sidings. The cables in the view above operate the points which control access from this siding to the main line. These days it is occasionally used to store works vehicles, like the track tamping machine below which I saw there in 2021. It is fenced off from the platform; passenger trains never run into here, though occasionally a passenger train has been stored there.

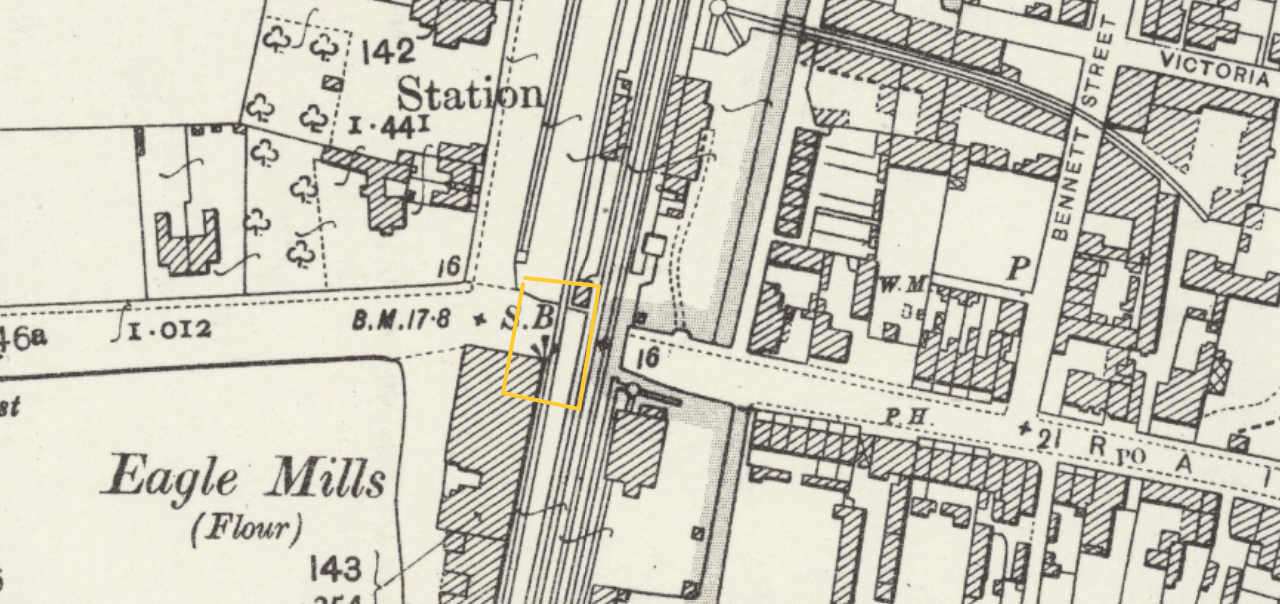

This track used to extend across the road into what is now the Heygates flour mill as you can see below.

That connection disappeared some time in the mid 20th century. But if you look really closely you can still see rails embedded in the concrete at the mill just across the road. You can see them in the photo below right next to the grey doors with the grilles. You can also see another very short section on the other side of the building when you pass through on the train.

And more hints of Downham’s goods yard can be found at what is now a veterinary practice next to the car park; engraving in a lintel above a window on the side of the building suggests that it was once the office for the goods yard.

On Platform 2 is this waiting room with a small office attached. I like it!

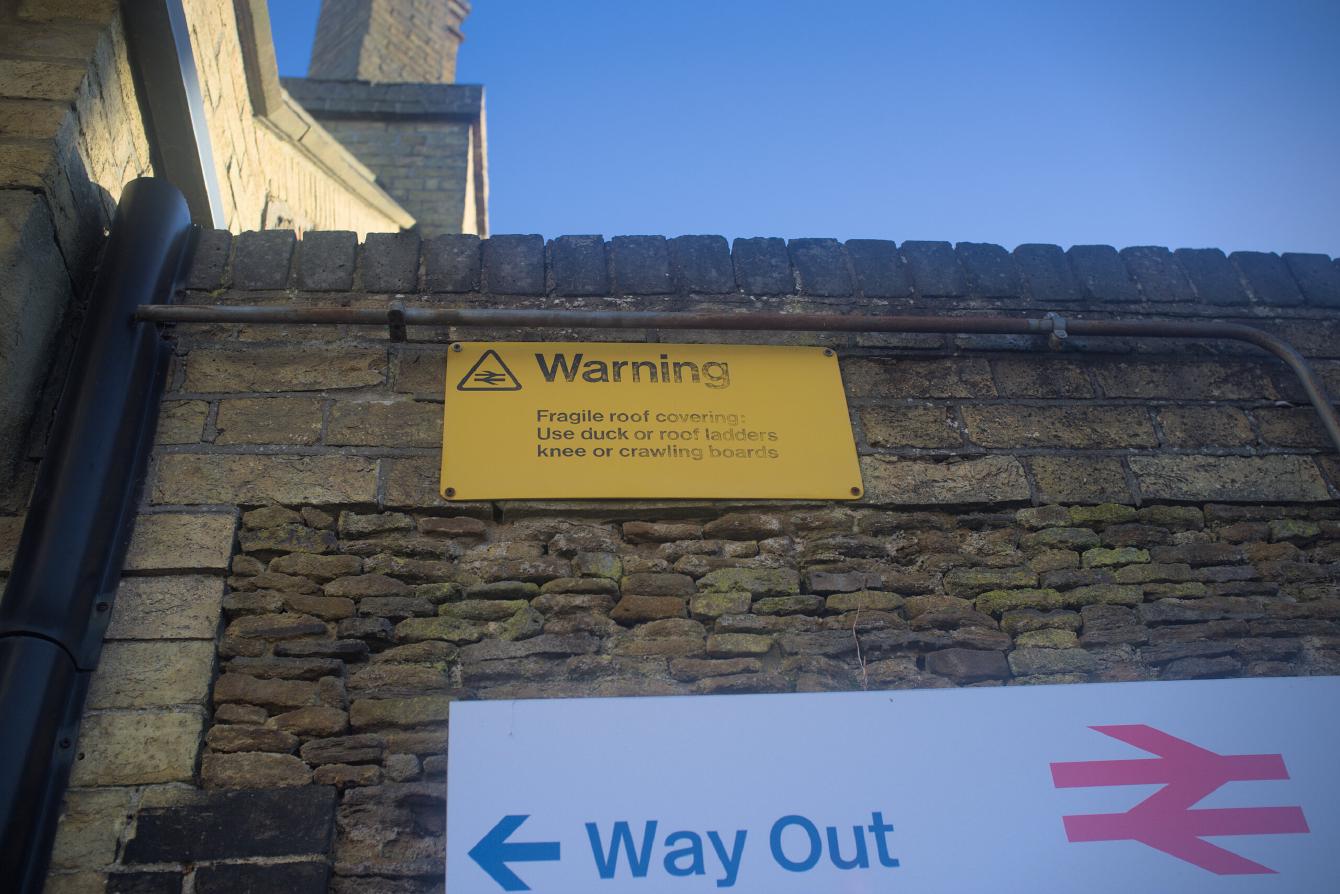

That’s hard to miss, but there’s a secret which most people would miss. On the left side of the building in this photo, just under the information screen, is a British Rail-era sign warning of a fragile roof.

Further up platform 2 are two mirrors that are original Network SouthEast survivors.

I call them Network SouthEast survivors not just because they are big and painted red; they tell the story of a particular era, inseparable from Network SouthEast, of this station’s history. These mirrors were for the driver to check the platform for anyone still attempting to board and other unsafe things, before closing the doors to move the train away. These weren’t necessary in the pre-electrification era, because trains carried guards who would check these things and signal to the driver when it was safe to move away. The Class 317 multiple units (and later the 365s) of the electrification era were one-person-operated and did not carry guards, necessitating the big mirrors. Today’s Electrostar units have cameras which makes these mirrors less necessary.

The largest of them, in the foreground above, were for the 4-coach trains that ran most services before late 2020. In the distance, you can see another towards the end of the platform for the 8-coach trains that occasionally ran services before 2020 and after that took over all of them. So the one in the foreground is twice an artifact of a period of time; post-electrification, but before the much longer trains that run today.

Let’s move to Platform 1 next. Back in the day, there was a foot crossing behind this fence; in fact, a longer time ago it was the only way for pedestrians to exit Platform 2. That had a light telling pedestrians when it was safe to cross and when it was not, and that was a system that depended on people being sensible. After “persistent, deliberate misuse”4 it was closed in 2011. So now we have to use the Station Road level crossing, and that is why we can’t have nice things.

Still, the road route allows getting a good view of a signal box from 18815, and that’s a pretty good view.

Signal boxes are an endangered species these days, and the Fen Line is fortunate to have four of them north of Ely. This GER Type 2 box is a Grade II listed building; it was identified as one of the most important ones to preserve when Network Rail announced their intent to retire all the traditional signal boxes on the network.

But that’s the obvious stuff. Around here, we like the secrets! If you look up at the sign on the road side of the signal box you can peek into two different eras.

From a distance, it’s obvious that this is an original Network SouthEast sign – and that demonstrates just how thorough and fast the Network SouthEast rebranding was thoughout the network, in that even a minor signal box got the NSE treatment. There’s your window into the late 1980s.

But underneath the text, the classic red-blue-grey NSE flash has been covered over with WAGN branding. That was West Anglia Great Northern, a post-privatisation company that ran services on the Fen Line from 1997 to 2006. There’s your window into the early privatisation era, when Network SouthEast branding was an artifact of the near-past; something just about old enough to be out of fashion. Now the station loudly celebrates Network SouthEast in ever corner, and the circle of life is complete.

In 20 years will we see stations getting WAGN makeovers? Trains on heritage lines getting WAGN liveries? Probably not. (A shame; I think the early livery with red doors was pretty sweet.)

And so that brings us to the main station building. The incidentals have changed a little and the environment around it has changed a lot over the years, but as with the waiting room on the other platform there’s little about the building itself that a Victorian passenger would not recognise.

Take a moment to admire the carrstone walls and the chimneys.

And then take a look at the canopy to see some Rail Alphabet.

A very close look shows that these were originally Network SouthEast blue, but have been painted over black – another example of the Network SouthEast association being something that, in the past, was to be literally covered up rather than celebrated as loudly as it is at this station today. (The three-bar flash that was once next to it was removed a long time ago.)

Nearby is another relic of a different time.

I’m talking about the phone box, though one could almost make a case for the post box as well. That’s a KX100 phone box, an artifact of the mid-1980s as much as the Network SouthEast branding is.

Yet, this one survives because it is difficult to remove, not because everyone thinks KX100 boxes are worth saving. They’re just about old enough to be unfashionable, but not old enough to be considered the subject of nostalgia - just as Network SouthEast was when the WAGN branding was slapped across the stripe on the signal box. Because of the intentionally unadorned, featureless design of these boxes, they may never be considered a classic. Even its fans only advocate saving three of them.

On to Platform 1, and a very clear indication that this platform was once less than half the length it is today.

The front end of the platform is brick-built, but beyond the point photographed above it’s of fairly crude wooden construction, demonstrating that it’s a later addition. I don’t know the exact date of the extension, but you can see the shorter version of the platform below in a photo by Rail-Online, likely taken in the early 1980s (the signs use the 1981-onwards “Downham Market” name, rather than “Downham”). A class 47 is passing over the points for a siding which occupied the space where the wooden extension is today.

Platform 2 looks like it has always been of its current length; it is of a single construction method.

Now, we could go look at the very nice canopies on platform 1, with their trefoil-adorned brackets (likely dating from the 1989 refurbishment)…

…and I did. But the nerdy thing to do is look at the very top right of that photo and notice that there is another British Rail-era sign warning of a fragile roof.

Right under that, there is a post box (not in use anymore) embedded in the wall, with the cypher of King George VI dating it from 1936 to 1952.

The toilets were locked when I visited (it was Christmas Day morning), but last I looked there was one of my own photos covering the entirety of one of the stalls in the gents. Now that’s a cool secret!

One last picture. My strongest memories of Networth SouthEast from when I was young were at night. Me and my mum and my brother did lots of weekend trips to the South East of England.

Most of those were taking advantage of cheap P&O crossings from Dover to Calais. They returned the same day, and that meant the trains back to London (that is to say, Network SouthEast) were mainly at night.

And so when I have cause to be at Downham Market station in the dark…

…it feels not just like a nice tribute, but a different time to me, and all it needs is the sound of that clock and a slightly-tired but brightly-painted slam-door EMU to roll in. And that, is all very nice.

-

See Mike Beckett’s intro to the book The Cambridge to King’s Lynn Line. ↩︎

-

A May 1985 timetable has these departure times from Downham Market to Cambridge or London: 06:56, 08:06, 09:06, 11:21, 13:11, 16:16, 16:54, 17:56, and 19:21. ↩︎

-

It didn’t even need much time; the 22 June 1993 Lynn News reported a 50% increase in usage since electrification was completed the previous year. ↩︎

-

According to Network Rail at the time, there were “on average 13 incidents each day of pedestrians crossing when the red warning lights showed. On one day, 17th October 2010, the crossing was misused 54 times between 8am and 6pm.” ↩︎

-

The plaque at Downham Market station building claims the date is 1888. Heritage England claims 1881, and puts this in the category of GER Type 2 boxes from the 1877-1882 period, so that is the date I will choose. ↩︎